Polar Satellite Altimetry: Keeping a space eye on climate change

I interviewed Chris Rapley, ESSC chair and Professor of Climate Science at University College London, to discuss the future path of Polar Satellite Altimetry and the ESA CryoSat mission.

By Shorouk ElkobrSI

July 05, 2021

POLAR REGIONS AFFECT US ALL

For most people, Earth’s polar regions seem remote icy wildernesses, of little relevance to day-to-day life. Yet changes that are taking place there are affecting us all. The Arctic is warming three times faster than the rest of the planet, and the resulting losses of sea ice, snow and permafrost are changing climate and extreme weather events in ways that extend to lower latitudes. The massive polar ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica are melting six times faster than in the 1990s, pouring ice and water into the oceans that contribute to rising sea levels worldwide.

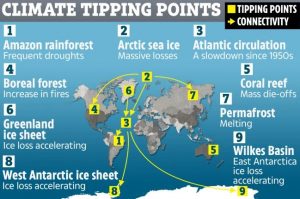

Within the climate system, there are ’Tipping Points’ – thresholds of irreversible change. Many of these are located in the cryosphere. “The Arctic and Antarctic are key pieces of the climate jigsaw. We have to understand them to understand how the whole system works. And thereby, to answer what political decisions need to be made,” explains Rapley.

MONITORING POLAR REGIONS FROM SPACE

In situ field research in the polar regions is tough, hazardous and expensive. Access in the cold and darkness of the polar winter is very restricted. Polar orbiting satellites, especially those carrying radars that can ‘see’ through clouds and operate at night, offer a transformative ‘window’ on the nature and behaviour of Earth’s icy zones.

Following early results from instruments on Skylab and the US missions Geosat and Seasat in the 1970s, Rapley led a European Space Agency (ESA) funded Study of Satellite Radar Altimeter Operations Over Ice-covered Surfaces. The study, published in 1983, paved the road for collaborative research in polar altimetry. It included 23 scholars from various institutions, including CNES, the British Antarctic Survey, Scott Polar Research Institute, and the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory.

The study concluded that satellite altimeter observations would allow the vast expanses of polar ice to be regularly profiled with high vertical resolution. It was anticipated that the data would show that global warming results in greater snowfall, which thickens some parts of the central Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets. In contrast, the warming of the oceans and atmosphere impacts the edges of ice sheets could cause rapid thinning and ice discharge. By combining data from models, satellite & airborne remote sensing, and field observations, climate research can be leveraged. Thus, satellite altimetry significantly disentangles the climate-related variations in remote polar regions.

THE CRYOSAT MISSION

During eleven years orbiting Earth, ESA’s Explorer mission, CryoSat, has provided a wealth of information about the changes in the ice sheets that blanket Greenland and Antarctica. The design of CryoSat’s altimeter has also allowed a step change in the estimate of Arctic sea ice thickness, using measurements of floe freeboard. CryoSat-2 provides unequivocal evidence about ice loss from the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets, and the seasonal and year-to-year variations and decline in the volume of sea ice in the Arctic Ocean.

After the failure of the CryoSat-1 launch in October 2005, the rapid CryoSat-2 build and launch in 2010 received a resounding response and support. In June 2021, the European Space Agency celebrated more than a decade of the CryoSat-2 satellite operations. During the CryoSat 10th anniversary conference, Chris Rapley co-chaired a session on the future of Altimetry along with Mark Drinkwater, Head of Earth & Mission Science Division at the European Space Agency (ESA). The session welcomed Valérie Masson-Delmotte, co-chair of IPCC Working Group 1 and Angelika Humbert, head of the working group on ice sheet modeling at the Alfred Wegener Institute who presented focal polar climate research gaps. It included Laurent Phalippou, IT operations director at Thales Alenia Space who introduced new satellite technologies. In addition, Andy Shepherd, Principal Science Advisor of ESA’s CryoSat mission, discussed prospects of polar altimetry.

ICE ALTIMETRY FOR THE FUTURE

The Copernicus Polar Ice and Snow Topography Altimeter (CRISTAL) mission is planned to launch in late 2027. However, with CryoSat-2 well beyond its design life, despite careful management by the ESA ground teams and engineers, there is a growing risk of technical failure and a consequent gap in observational coverage. No other altimeter mission reaches the 88° latitude of the CryoSat and CRISTAL orbits. The timing is critical, as during this period accelerating changes are anticipated in the loss of Arctic sea ice and an increase of East Antarctic snowfall in the observing zones that will become ‘blinded’ in the interim.

Altimetry missions need policy support, funding, and consolidated efforts. Andy Shepherd argues that there is a lack of coordination between climate science experts’ assessment reports and Earth observation satellite missions’ reports. To bridge this expertise gap, representatives from both fields need to sit at the same discussion table.

Polar-orbiting satellites have transformed the way we study polar regions. It is no longer too difficult, too hazardous, or too expensive to have year-long polar data. But the question remains: where are we heading over the next few decades in terms of the use of altimeters to study the rapidly diminishing and changing ice?

“In the short term, we look to the key agencies concerned to make every effort to avoid a gap in these critical measurements. The ESSC is well-positioned to be the voice of the community. We offer a science-policy channel by which this discussion between ESA, the EC and the community can be held to agree and pursue actions to ensure continuity of coverage,” concludes Rapley.

Twenty-five years of radar altimetry development and satellites orbiting Earth have enhanced our understanding of the present state and likely future of the Cryosphere. However, without consolidated efforts and effective political decisions to continue and deploy polar altimetry missions, a key window on the poles could be temporarily closed.